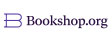

THE DOVE IN THE BELLY

by Jim Grimsley

Two young people undergo an awakening, brought about in each by the other, in the midst of a violently beautiful spring and summer in Chapel Hill. They are children of the seventies, born into an era when gender norms are shifting but still a time when a person who is different feels the need to hide their nature; but for Ronny and Ben, their connection is what matters. They find a refuge in a room in Miss Dee’s boardinghouse and something unfolds in their lives that they can’t deny or turn away from. Writing their story took me back to those years in my own life when I landed in my college dorm room, having barely survived my early years, facing the isolation of my gender difference, looking out in awe at the wide world of university and the wider world beyond it. Knowing my life would be forever colored by the fact of my sexuality, and learning to take one step after another into my adult future.

Paperback coming June 4 2024