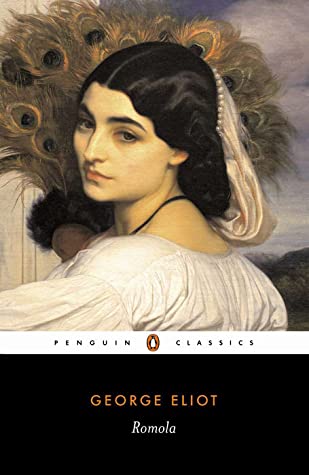

Romola by George Eliot

There are only a couple of George Eliot books that I had not read by the age of thirty and this is one. It was a revelation in that it was a book of hers that I could dislike, and the novelty of that is what kept me reading. I have seen it called her best novel, admittedly by only one of her contemporaries, and kept thinking about that while I endured the reading. She herself is said to have claimed that each sentence in the novel is as good as all her skill could make it, though I am paraphrasing and maybe overstating. The sentences are certainly fine enough, and Eliot is a good writer even she is not at her best. What was most interesting here was to see her undertake an historical novel, and the idea of that was also a bit revelatory, since all her novels read like history from this distance. For the first time I understood her to be a modern novelist in the context of her time and place. Though she often writes about an era thirty or forty years in the past, as her introductions to her books often reveal. What I mean is that as a writer she was dealing with contemporary people and issues, not about the remote past, which is what I as a reader had always felt from her. This explained some of what was missing from Romola. It is certainly a good story and should be compelling except that one feels Eliot straining at the creation of the world, constantly convincing herself of the reality of historical Florence, and at pains to record all the details of her research. What is missing from the book is her sense of humor. In every other novel there are comic passages, careful touches of dialog that reveal the person speaking, like the aunts in The Mill on the Floss, or Adam’s mother in Adam Bede. She is a masterful creator of background characters and low-minded people, and these touches are vital to the representation of the foreground, the heroes and heroines, the virtuous, the sublime. This background is mostly missing from Romola. The characters have little voice. They speak in translation, as it were, and not in themselves. Which leaves virtue (Romola) and vice (Tito) to carry the book on their own, and they make a poor job of it. The end of the book, with angelic Romola among the plague victims, adored and all that, feels a bit laughable, at least to me. I am certainly not accustomed to thinking of George Eliot in these terms, as having written a not-good book. Reading the book humanized her for me. Even great writers have their failures. There’s no reason to gloat over this, though I suppose that’s what I’m doing. But there is a certain humanizing quality in the knowledge.